Can a watermelon be grown in the shape of a square? What do Olympic athletes like Michael Phelps eat for breakfast? Which island nation produces the most lamb in the world? Consumers interested in pulling back the curtain on our food system will get these and many other questions answered at “Our Global Kitchen: Food, Nature, Culture.” The exhibition, on view now at the American Museum of Natural History, explores how our food is produced, distributed and eaten. I checked it out during a recent visit to New York City.

“Our Global Kitchen” starts with a 6-minute movie that demonstrates just how vast, complicated and far-reaching our food system is. While reporting for Harvest Public Media, I’ve seen firsthand that farmers and ranchers are on the front lines of this system. But the film and exhibit really helped me put their roles into perspective. Thought-provoking statistics reveal that while farmers produce almost 30 percent more food than they did two decades ago, one in eight people around the world still go hungry. Thousands of crops have been bred in the history of farming. Yet 40 percent of our land is used to grow just three of them: wheat, corn and rice. Seventy five percent of agricultural land world-wide is used to raise livestock and 35 percent of crops grown are used to feed that livestock. About 42 million children are overweight.

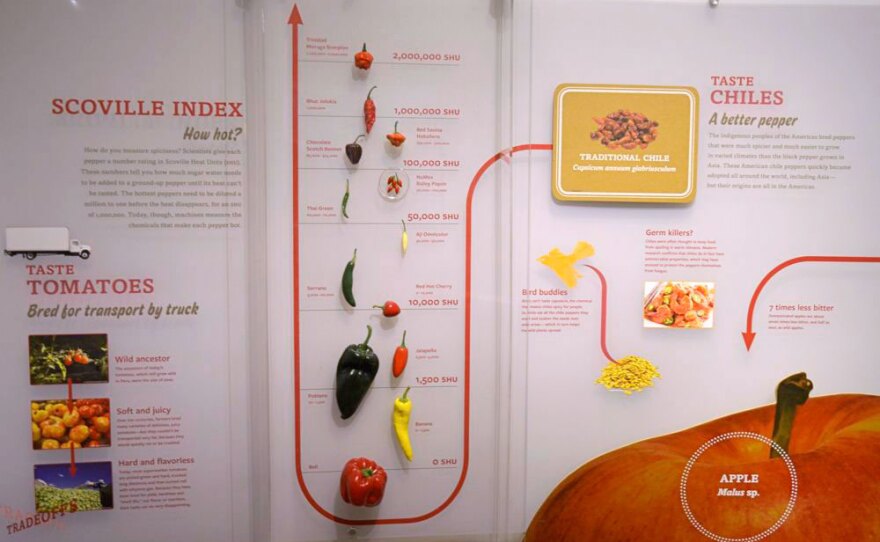

After the film, the exhibit turns to familiar foods like fish and potatoes and focuses in on how they’ve been modified over time. In Japan, for example, farmers transformed the spherical look of watermelons by growing them in square glass boxes. We learn that chili peppers got their spiciness ratings from the Scoville Heat Unit scale, which was created in 1912. Visitors are asked to consider what the future of farming might hold through looking at the pros and cons of test-tube beef grown from animal stem cells, disease-resistant bananas and vertical gardens built inside skyscrapers.

The next section of the show takes visitors back to a 16th-century Aztec market and the staples of that cuisine -- like chocolate and tomatoes -- that are now so ingrained in our diets. A computer game called Food Ships demonstrates how lambs raised in New Zealand, the world’s biggest exporter of that meat, end up in our grocery stores and restaurants. A towering sculpture of trash is meant to represent the staggering amount of food an American consumer throws out each year: 414 pounds.

Then there are cooking artifacts to peruse from the museum’s permanent collection, such as a miniature pottery stove from the Han Dynasties era, and smelling stations that waft sweet scents of popcorn and lavender to your nose with a push of the button. In an adjoining kitchen, visitors are encouraged to taste cherry jellybeans with their noses plugged to understand how taste and smell are connected. Recipes for West African groundnut, or peanut, soup are offered up, as are samples of food and drinks from around the world like Vietnamese coffee sweetened with condensed milk.

The exhibition wraps up with meals recreated from the past. First, there’s the ancient Roman cuisine of Livia Drusilla, the wife of the emperor Augustus, which is composed of olives, eggs in pine nut sauce and salted sea urchins. Then, ices made from damsom plums, currants, caramel, cream and sugar eaten by the writer Jane Austen at home in Kent. The Mongolian ruler Kublai Khan ate flower dumplings, steamed mutton, fish and green onions. Hungry yet? Also featured is the last meal of cattle herder Ötzi -- dried wild plums, goat and bread – who died 5,000 years ago. And a favorite breakfast of swimmer Michael Phelps, which amazingly included a five-egg omelet and a fried-egg sandwich, french toast, pancakes and coffee. All this reveals how much cuisine has changed over time, how it’s affected by place and class, and how seeing it in front of you really does make you hungry.

Although “Our Global Kitchen” doesn’t dig too deeply into any one of the probing questions it poses, the exhibition does give a solid overview of our global food system. And for people who don’t get to report on food production and agriculture every day as I do, this exhibit is critical in understanding, say, that milk and meat come from working farms, not simply from the grocery store. “Our Global Kitchen” makes a case for why the future of food is important, especially given that the world will have an estimated 9 billion people by 2050. Plus, learning that the world’s heaviest strawberry weighed a full half of a pound will make you a good asset to any trivia team.

“Our Global Kitchen” at the Natural History Museum runs through Aug. 11.